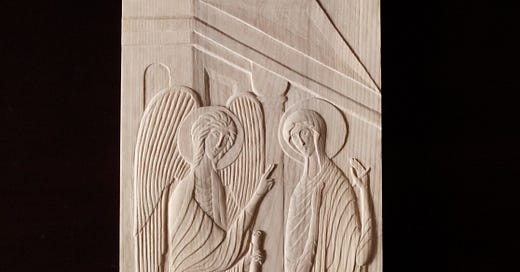

The Annunciation

A recently finished carving of the Annunciation, delving into the process with some thoughts on tradition.

This carving begun when I was very new to Orthodoxy. I started creating this work a year or so ago, time got the better of me and it lay unfinished. This made me think of a quote from a book I came across, called Miro: I work like a gardener. Depicting a conversation between Miro and the French artist, author, and art critic Yvon Taillandier one November afternoon in 1958.

“If a canvas remains in progress for years in my studio, that doesn’t worry me. On the contrary, when I’m rich in canvases which have a point of departure vital enough to set off a series of rhythms, a new life, new living things, I’m happy.

I consider my studio as a kitchen garden. Here, there are artichokes. There, potatoes. Leaves must be cut so that the fruit can grow. At the right moment, I must prune.

I work like a gardener… Things come slowly… Things follow their natural course. They grow, they ripen. I must graft. I must water… Ripening goes on in my mind. So I’m always working at a great many things at the same time.”

I am very fond of this thought, the studio as a kitchen garden. I suppose it rings true to me as I know I am a slow man. Rushing or frantic things bring out a rash. Seeds sprout their growth and need the time and nutrients to grow. The nature of carving is a slow man’s game. I always think it is important for new works to have a gestation period. With this carving, I think for myself it was the beginning of trying to know the Mother of God. Back when I started this, my knowing was infinitesimally small. After 2 years of going to an Orthodox Church I would say it still is small. We can get analytical about the Mother of God, pondering on the significance or the idea of her, but it’s not the same as a lived experience. This unfolds each day. I remember hearing from someone in the Church an old phrase along the lines of the Mother of God sits on a throne in Heaven, but you will never find her sat there as she is always so busy helping. This may ring true to all mothers out there.

When it came to the icon itself, I would say it has 3 key components to it.

When I saw the image of this wonderfully carved icon, I wanted to respond. I was incredibly fond of the tall and narrow nature of the panel, which forces this closeness between the Archangel Gabriel and the Mother of God. I also thought the depiction of the temple was wonderfully done. If you would like to read more about the carving in its setting of a chair, here is a good article on it.

From this initial spark, I set to looking at other works to feed into this piece. This points to a dynamic of working in a tradition, there is a great respect and admiration for the works of old, and also for the limitations in place to keep the foundations standing. I suppose tradition is either a stone stuck at the bottom of the ocean floor or a living and breathing thing. New works need new breathe to keep them alive.

Which leads to the next component, which is the Romanesque and Anglo-Saxon period. This points to the dynamic of a new tradition, though being in the past. The work created in that time was out of Apostolic Christianity finding it’s roots across Europe, even if it was a bit wild and messy. The influence and rootedness in tradition is clear in their depictions, yet there is a freshness and locality to the work. Showing one tradition merging with another, and beyond that, a faith inhabiting the heart of people. It wasn’t the case where they felt they had to immaculately copy Byzantine modes in the creation of sacred art, but taking the language and synthesising it with their own culture.

Prior to the Romanesque in Britain was the of course the Anglo-Saxon period. These two certainly fed each other and mingled. The Saxon Christian tradition over in Britain would have been more similar than different to how we know Orthodoxy today, a very beautiful form of Christianity came to life and flourished. This can be seen in the saints, their poetry and scant remains of written works, alongside the manuscripts and carvings that have managed to survive the unrelenting perils of conquest, invasion and iconoclasm. In the creation of artworks, It was a merging of two natures, perhaps due to the Archbishops in both York and Canterbury. The earliest stemming from the Irish and Scottish, trickling down to the North of England with Germanic, Byzantine and Celtic influences, later Scandinavian influence from Viking invasions, then a Latin tinge. You can see the move away from the more Celtic influence, as it gradually shifts to the more Byzantine and Latin modes, whilst still retaining a local charm.

There is a church in Breedon on the Hill in Leicestershire which has some remarkable remains of Anglo Saxon carving.

If you wish to explore some further examples, I shall direct your attention to here and here. Some recent trips taken to see some local wonders. The Church in Bradford-on-Avon is one of the most remarkable remains of Anglo-Saxon architecture.

Perhaps the most enduring works following this period are of course the mountains of masonry that the Norman conquest raised. Conquest is a messy affair… and to trace the resulting factors of influence is also messy. It isn’t so simple to say the Anglo-Saxons were thriving, and then on that fateful day of 1066, it all came to an end. It was much more transitional. Some scholars believe that the conquest resulted in the ruin of the fine flowering of Anglo-Saxon art and Christianity. Which there is a truth to, as there was enormous plundering of Anglo-Saxon churches and monasteries by the new Norman rulers in their first decades, and an imposing of Norman rule. Others believe that the conquest brought England into the mainstream of European development. I suppose the truth is somewhere in the middle. But the Saxon artists remained. And pre-conquest Saxon art didn’t disappear altogether. It did have influence on Norman art previous to the conquest and even well into the conquest.

The reason for exploring all this is to acknowledge that the Anglo-Saxon and Romanesque period is perhaps the closest link we have to a more Orthodox artistic tradition stemming from the British Isles. Studying the artistic pursuits that flourished during the Medieval period, it becomes clearer that there was an interconnected stream flowing to and fro Europe and beyond, bringing a universality to it, a more unified body rather than fragmented. We could step into any church from this period and recognise most of the poetic symbolic language used in the carvings and the murals. As the faith flourished, so did the creation of beauty.

As Orthodoxy is becoming further known and experienced in Britain and America, I can’t help but think of creators like myself wanting to find something that connects to our lineage and story, whilst not getting lost in the romantic nostalgia of the past. Or not detracting the importance of connecting to the 2000 years of gold that Orthodoxy has endured and thrived. This will of course take time and discernment, which can’t be rushed. In a way it is the attempt to do something new whilst doing nothing new at all. It is of a great sadness that so much of it was destroyed due to our confused periods of history. So we have a lot of work to do to get us back to scratch! But we must remain hopeful, the saints which were locked away by the Puritans are emerging again, over the past 150 years or so, the relics of a number of early English saints have either been miraculously rediscovered or returned from other countries. They are returning to our streets, the Apostle of Wessex, St. Birinus relics are kept at the church in Dorchester-On-Thames, and he has been seen at night walking the streets as if guarding his flock. The residents of Beverley near York have seen the holy Hierarch and Wonderworker John of Beverley strolling in the town. The Venerable Bede has appeared to people at his Shrine in Durham Cathedral. Miracles are happening through our old friends. Perhaps this points closer to how the art and beauty will come to flourish, the faith and the liturgy comes first, and the rest will follow.

The next component is one that is very difficult to be avoided, which is something the Medieval artist didn’t have, the internet! This is a strange time, to have access to all the art forms that have ever existed with a click of a button. Overall this is a difficult line to travel, finding the good stuff and avoiding the bad. The world of books and the screen suddenly opens all this up like a flood gate, and it does have effects on our psyche, ones we are only gradually starting to see. Compare going down to a bookshop, or scrolling endlessly on the laptop to going on a Pilgrimage across Europe to the likes of Rome or Jerusalem. A very different experience indeed. Needless to say, both have their qualities. Though there is much more humanity in pilgrimage!

I shall direct you to the work of Merab Abramishvili. I found this artist on the internet, I absolutely adore his work. It has fed my imagination to no end, I have been continually returning to his body of work since discovering him. Being from Georgia, there is most definitely an Orthodox tinge to his works, with many depicting Biblical themes. For him, one of the most influential works on him were the medieval frescoes from the Ateni Sioni Church. There is an acute delicacy to his works, the line work is immaculate. Some may call it unfinished, but this quality looks as if it has already sat on a wall for hundreds of years.

There are certain artists which you instantly connect to, it doesn’t have to be the works of one individual, but also a period or style. It is hard to explain, it is very much a visual and luminous response, connecting you to beauty. A magnetic hum that draws you in closer. This was most certainly the case with Abramishvili’s works for me, all of them. But I shall focus on his paintings of the dancers. I just found these pieces to be so unbelievably wonderful. The flowing and bellowing drapery fills the canvas, details are there, then they are not, the painted lines intermingle and flow seamlessly. There is a stillness and a movement to them all at once.

Perhaps it is a stretch to try connect the Annunciation with a dance, but it is a joyous moment. It was upon reading The Proto Evangelion of James, an apocryphal text recounting the things that happened before the ministry of Christ, such as the birth of the Virgin Mary, her service in the temple, her betrothal to Joseph, up to the birth of Jesus. It was this line when Mary was three years old entering the Temple that stood out to me.

“the Lord God sent grace upon her; and she danced with her feet.”

It was this line which I thought aha! Maybe there is a just reason for this portrayal. That perhaps there was some strange intuition working, of seeing the paintings of the dancers and thinking of the Mother of God.

That small line seemed very joyous to me, a small child being so overcome with grace the response is to do a little jig. It made me think of the Annunciation, where the grace is heightened beyond compare to the life of Christ coming into this world, how could you even begin to comprehend such a thing! The Messiah is finally coming, joy. I know not such a line appears in the story of the Annunciation in scripture, but this is the beauty of the icon, it can incorporate other elements which point to the poetic truth of the matter.

I knew this dancing posture couldn’t be done too overtly, that wouldn’t be right. Just a little hint. Dancing sits on a fine line of both positive and negative aspects, it is an act in the Bible that was used for praise and worship. Or it’s a force that can lead you astray, falling for the tunes of the pied piper, or succumbing to the call of the siren.

Jeremiah 31:4

“Again I will build you and you will be rebuilt,

O virgin of Israel!

Again you will take up your tambourines,

And go forth to the dances of the merrymakers.”

A line like this is celebratory. Dancing can be a very joyous thing, with a time and a place for it. “a time to weep and a time to laugh, a time to mourn and a time to dance”. It is a very beautiful act that unifies, it requires a coordination of the movements of your body with people around you. Dare I say there is an aspect of this in the Liturgy, the Priest leads and we respond.

With these aspects decided upon, I took to drawing directly on this tall and narrow piece of ash wood, I tried to capture this sense of still movement with the Mother of God, she is stood upright with her arms swaying upwards as if she is poising for the dance to begin, her robes sway gently below in this first movement. Their heads tilt towards one another in a reciprocal bow, the Archangel Gabriel comes holding the message, whilst blessing her. The direction of the hand is a sort of pointing, as if to say you have been chosen and you are invited. Which is something we are all called towards. Mary’s right hand is placed on heart as if to say I accept your invitation. In her left hand she holds a spindle of yarn which depicts the task she was assigned of preparing the veil for the Temple in Jerusalem.

My search to know the Mother of God still continues, and a series of works dedicated to her are now available on my website:

if you would like to own one of these works, please do get in touch.

I'm both startled and pleased to run across an Abramishvili reference here; I'm fond of his work, but I probably never would have heard of him if I hadn't lived in Georgia (that Georgia) for a couple years. And I love the connection you make between his dancing figures and that delightful scene from the Protoevangelium of James. I'll be musing on that for a while.