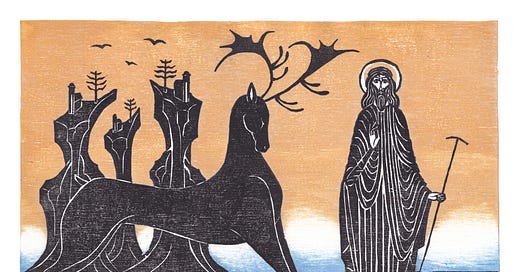

The initial idea for St Herman was to have him standing firm on an island with an island behind him. I liked this first sketch, I stuck to the composition, and it grew accordingly.

It seemed important to have these sort of floating islands behind him with chapels on. St. Herman is foundational in his work, the efforts by him and others were very important in bringing Orthodoxy to the Americas, and the islands/the ground are growing upwards, reaching towards Heaven from these efforts. Paul brought it to my attention that his monks lived on a series of islands, and paddled between them in canoes. These chaps were incorporated into the design. The animal chosen was a stag, I am unaware of any miraculous tales that are of the same ilk of the likes of St Cuthbert or St Colman, it just seemed appropriate for him to be stood beside one. I really enjoy the inspiration found from the brass rubbings which I explored in the previous print (read here). I thought I would approach this print with the same mind.

I stumbled across Bestiaries during an online research binge. They are phenomenal medieval texts, showing aspects of Christ within the animal kingdom and the natural world. The charm of them comes from the rich medieval mind seeing God in every act of creation. Perhaps today in the studying of animals, we verge on the side of the overly positivistic science, and forget to see the Creator in them. Yet these bestiaries certainly are a kind of science, if we get the meaning of the word right, stemming from the Latin and Greek, put very simply as knowledge. The Bestiary knowledge is of a different framework, a more mystical and mythic frame, pointing to another truth beyond the physical. Combining the physical, moral and spiritual, with a tale to be told about each animal. Which perhaps is more of an enticing read than the viscosity of a slugs mucus or something. The stags description in a 13th century text from the Arundel Bestiary, which was made in the east of England (possibly Norfolk), seemed appropriate for St Herman’s story:

‘The stag pulls a serpent up through his nose continuously, from a tree trunk or from a stone (for the serpent will go under it). He swallows it quite well. When he does this, he burns himself and has a burning pain inside from that venomous thing.

Then he rushes with great dexterity because of a thirst for fresh water. He drinks water greedily until he has completely recovered. The venom has no power to harm him — not at all.

He also casts away his horns in the wood or in the thorns and is rejuvenated thus — this wild animal — as you have now learned here.

The stags have another characteristic that should be in all of our minds. They are all of one mind because if they fetch food from far away and go across water, none will desert another in distress. Instead, one will swim in front and all the others will follow.

Whether he swims or wades, none in distress leaves another behind but places his jawbone on the haunch of another.

If it happens that the one who goes in front grows tired, all the others come with him and help to pull him. They carry him from the river bottom up to the land all healthy and sound and providing for his needs. They have this practice among them even when there are one hundred together.

We ought to consider the stag's habits. No one ought to shun another but instead love everyone as if he were his brother, be steadfast towards his friend, lighten him of his burden, and help him when he is in need.’

Perhaps a modern version of the bestiary would be a visual one like this, one of the most phenomenal and masterfully captured moments of wildlife. From the moment we are born, the serpents scent us, our instinct is to stay still until we are forced to move, and the chase ensues. We most likely get ensnared by the serpents bite, but the mercy of God will always be there to get us out, and guide us home.

If would like to purchase the print of St Herman, there are some available here: