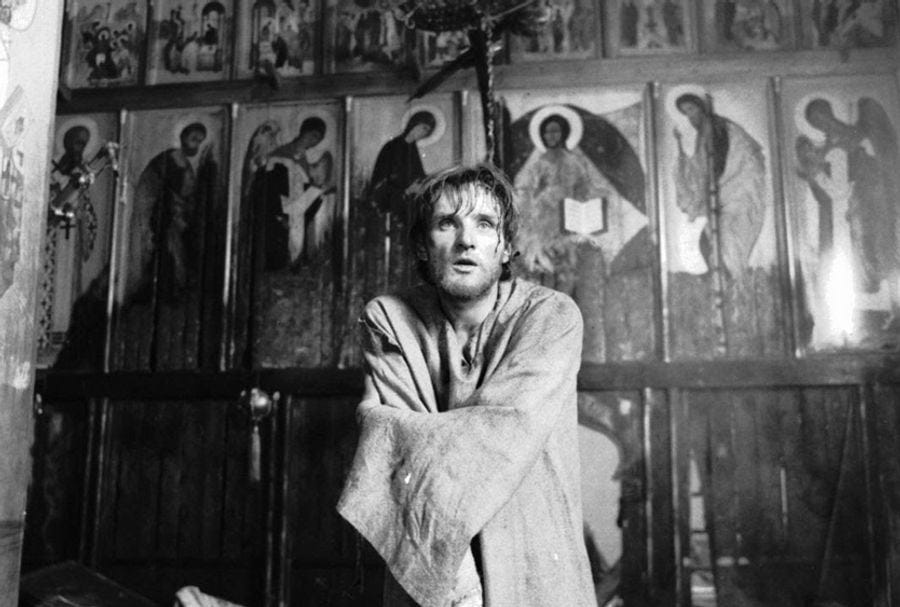

I have recently been reading ‘Sculpting in Time’ (Released in 1985) by the great film director Andrey Tarkovsky. I have a lot to be grateful to Tarkovsky for, firstly for some of the greatest films I have ever seen, secondly, he made me aware of Andrei Rublev, and thus his masterpieces, which have slowly come to shape my shift in purpose and thoughts around art and faith. I have yet to watch his entire filmography, I have seen Andrei Rublev, Stalker and Nostalgia. All were astounding and radiantly poetic, rich in beautiful imagery and thought. I think I haven’t got round to watching the rest of his films due to the daunting sense that they require my whole being to be engaged in watching, and it’s almost as if I have to do some stretches or something before, they certainly aren’t for a casual watch!

Upon reading this tremendous book, which I highly recommend, (even if you don’t like cinema) I thought the conclusion he had come to was incredibly poignant. It is aligned with that same common thread that more and more people are starting to recognise. A lot of the readers on this substack have come here from the Abbey of Misrule (Which I am incredibly grateful for your support!), I feel this certainly adds to the chain of thought arising from Paul and you all. I thought it may be good to share a large portion of it on here with you, as Tarkovsky is mostly known to cinema and film buffs, and perhaps many haven’t come to know his poetic sensibility to life. It doesn’t spoil the book, or detract from the whole read, as it’s the kind of book you can start at any chapter and be enthralled by his wonderful Russian clarity.

Sculpting In Time

Today it seems to me far more important to talk not so much about art in general or the function of cinema in particular, as about life; for the artist who is not conscious of its meanings unlikely to be capable of making any coherent statemen in the language of his own art. I have therefore decided to complete this book with some brief reflections on the problems of our time as they confront me now; on those aspects of them that seem to me fundamental, with a bearing beyond the present moment, to the meaning of our existence.

In order to define my own tasks, not only as an artist but, above all, as a person, I found myself having to look at the general state of our civilisation and the personal responsibility of every individual as participant in the historical process.

It seems to me that our age is the final climax of an entire historical cycle, in which supreme power has been wielded by the ‘grand inquisitors’, leaders, ‘outstanding personalities’, who were motivated by the idea of transforming society into a more ‘just’ and rational organisation. They sought to possess the consciousness of the masses, instilling them with new ideological and social ideas, bidding them reform the organisational structure of life for the sake and happiness of the majority. Dostoievsky had warned people of the ‘grand inquisitors’ who presume to take upon themselves the responsibility of other people’s happiness. We ourselves have seen how the assertion of class or group interests, accompanied by the invocation of the good of humanity and the ‘general welfare’, result in flagrant violations of the rights of the individual, who is fatally estranged from society….

Throughout the history of civilisation, the historical process has essentially consisted of the ‘right’ way, the ‘correct’ way - a better one every time - conceived in the minds of the ideologues and politicians, being offered to people for the salvation of the world and the improvement of man’s position within it…..Concerned for the interests of the many, nobody thought of his own in the sense preached by Christ: “Love your neighbour as yourself”. That is, love yourself so much that you respect in yourself the supra-personal, divine principle, which forbids you to pursue your acquisitive, selfish interests and tells you to give yourself, without reasoning or talking about it; to love others. This requires a true sense of your own dignity: an acceptance of the objective value and significance of the ‘I’ at the centre of your life on earth, as it grows in spiritual stature, advancing towards the perfection in which there can be no egocentricity. In the fight for your own soul, fidelity to yourself demands unceasing, single-minded effort. It is so much easier to slip down than it is to rise one iota above your own narrow, opportunist motives. A true spiritual birth is extraordinarily hard to achieve. It is all too easy to fall for the ‘fishers of human souls’; to abandon your unique vocation ostensibly in pursuit of loftier and more general goals, and in doing so to bypass the fact that you are betraying yourself and the life that was given to you for some purpose.

The pattern of social relationships has formed in such a way that it is possible for people to ask nothing of themselves, to feel exempt from all moral duty, and only to make demands of others, of humanity at large. They can invite others to be humble and sacrifice themselves, to accept their role in the building of the future, while they themselves take no part in the process and accept no personal responsibility for what is happening in the world. A thousand ways can be found to justify this non-involvement and the fact they don’t want to give up their narrowly selfish interest in order to work for the nobler goal of their true vocation; nobody wants, or can bring himself, to look soberly into himself and accept that he is accountable for his own life and his own soul. On the premise that we are all ‘together’, in other words that mankind is in the process of constructing some kind of civilisation, we constantly turn away from personal liability and without realising that we are doing so, shift on to others all responsibility for what happens. As a result, the conflict between the individual and society becomes increasingly desperate, and the wall of estrangement between the person and humanity grows ever higher.

The individual either becomes the instrument of other peoples ideas and ambitions, or else he himself becomes a boss who shapes and uses other people’s energies with no regard for the rights of the individual. The idea that everyone is responsible for himself seems to have vanished, to have fallen victim to a misconceived ‘common good’, in the service of which man acquires the right to be treated with a total lack of responsibility…. From the moment when we entrusted to others the solving of our own problems, the rift between the material and the spiritual has been growing. We live in a world governed by ideas which other people have evolved, and we either have to conform to the standards of these ideas or else alienate ourselves from them and contradict them- a position which becomes more and more hopeless.

It is, you will agree, a bizarre and grim situation…

If a persons sense of responsibility for the future of society is not based on an inner conviction of the part he has to play, if he merely feels entitled to make use of other people, directing their lives for them and indoctrinating them with the idea of their role in the development of society, then the discord between the individual and society can only become more bitter.

Freedom of will must mean that we have the capacity to access social phenomena as well as our relationships with other people; to make a free choice between good and evil……It is obvious to everyone that man’s material aggrandisement has not been synchronous with spiritual progress. The point has been reached where we seem to have fatal incapacity for mastering our material achievement in order to use them for our own good. We have created a civilisation which threatens to annihilate mankind. In the face of disaster on that global scale, the one issue that has to be raised, it seems to me, is the question of man’s personal responsibility, and his willingness for sacrifice, without which he ceases to be a spiritual being in any real sense.

I mean that spirit of sacrifice which must constitute the essential and natural way of life of potentially every human being: not something to be regarded as a misfortune or punishment imposed from without. I mean the spirit of sacrifice which is expressed in the voluntary service of others, taken on naturally as the only viable form of existence.

And yet in the word today personal relationships are all too often based on the urge to grab as much as possible from the next person as we jealously protect our own interests. The paradox of such a situation is that the more we humiliate our fellow-men, the less satisfied we feel and the greater our isolation becomes. Such is the price of our sin in failing to turn, of our own free choice, to the heroic path of our own human fulfilment, accepting it with our whole heart and will as the one true way and the only thing we desire. Anything less than such total acceptance will exacerbate the conflict between the individual and society; a man will see society as the agency of a violence done to him.

For the moment we are witnessing the decline of the spiritual while the material long ago developed into an organism with its own bloodstream, and then became the basis of our lives, paralysed and riddled with sclerosis. It is clear to everyone that material progress doesn’t in itself make people happy, but all the same we go on fanatically multiplying its ‘achievements’. We have reached the point where, as Stalker says, the present has essentially merged with the future, in the sense that it contains all the preconditions for immanent disaster; we recognise this and yet we can do nothing to stop it happening.

The connection between man’s behaviour and his destiny has been destroyed; and this tragic breach is the cause of his sense of instability in the modern world. Essentially, of course, what a man does is of cardinal importance; but because he has been conditioned into the belief that nothing depends on him and that his personal experience will not affect the future, he has arrived at the false and deadly assumption that he has no part to play in shaping his own fate…. man should go back to believing in his soul and it is suffering, and link his own actions with his conscience. He has to accept that his conscience will never be at rest as what he does is at variance with what he believes; and recognises this through the pain of his soul as it demands he acknowledge his responsibility and his fault. This precludes self-justification through convenient and easy formulae about the fatal influence of other people - never of ourselves - upon what is happening. I am convinced that any attempt to restore harmony in the world can only rest on the renewal of personal responsibility….

Once man had turned history into a soulless and alienated machine, it immediately started to require human lives as the nuts and bolts that would keep it going. Consequently man has come to be regarded first and foremost as a socially useful animal. (The only question is how to define social usefulness.) By emphasising the social usefulness of someone’s activity to the point where the rights of the personality are ignored, we commit an unforgivable mistake and create all the preconditions for tragedy.

The issue of freedom raises the question of experience and upbringing. Modern man in his struggle for freedom demands personal liberation in the sense of license for the individual to do anything he wants. But that is an illusion of freedom, and man will only be heading for disenchantment if he pursues it. It takes a long, hard struggle on the part of the individual to liberate his spiritual energies. Upbringing has to be superseded by self-disciple: otherwise he will only be capable of understanding his newly acquired liberty in terms of vulgar consumerism.

In this respect, the situation in the West gives us ample food for thought. Incontrovertible democratic freedom exist side by side with a monstrous and self evident spiritual crisis affecting ‘free’ citizens. Why, despite the freedom of the individual, does the conflict between the person and society exist here in such an acute form? I think that the experience of the West proves that freedom cannot be taken for granted, like water from a spring that doesn’t cost a penny and demands no moral effort from anybody; if that’s how he sees it, man can never use the benefits of freedom to change his life for the better. Freedom is not something that can be incorporated into a man’s life once and for all: it has to be constantly achieved through moral exertion.…. We have become used to paying for everything with other people’s toil and other people’s suffering- never our own. We refuse to take into account the simple fact that ‘everything is connected in this world’; nothing can ever be fortuitous since we are endowed with free will and the right to choose between good and evil.

Naturally the opportunities for asserting your free will are limited by the will of others, but it must none the less be said that the failure to be free is always the result of inner cowardice and passivity, of lack of determination in the assertion of your will in accordance with the voice of conscience.

In Russia people are fond of repeating Korolenko’s dictum to the effect that ‘ man is born for happiness like a bird for flight.’ It seems to me that nothing could be further from the basis of human existence than those words. I can never see what meaning the concept of ‘happiness’ as such can actually have for any of us. Does it mean satisfaction? Harmony? But a person is never satisfied, for his sights are never ultimately set on specific finite ends, but on infinity itself.

In this situation it seems to me that art is called to express the absolute freedom of man’s spiritual potential. I think that art was always man’s weapon against the material things which threatened to devour his spirit. It is no accident that in the course of nearly two thousand years of Christianity, art developed for a very long time in the context of religious ideas and goals. It’s very existence kept alive in discordant humanity the idea of harmony.

Art embodied an ideal; it was an example of perfect balance between moral and material principles, a demonstration of the fact that such a balance is not a myth existing only in the realm of ideology, but something that can be realised within the dimensions of the phenomenal world. Art expressed man’s need of harmony and his readiness to do battle with himself, within his own personality, for the sake of achieving the equilibrium for which he longed….

Given that art expresses the ideal and man’s aspiration towards the infinite, it cannot be harnessed to consumerist aims without being violated in its very nature. The ideal is concerned with things that do not exist in our own world as we know it, but it remind us of what ought to exist on the spiritual plane. The work of art is a form given to this ideal which in the future must belong to mankind, but for the moment has to be fore the few, and in the first instance for the genius who made it possible for human awareness, with all its limitations, to be in contact with the ideal incarnate in his art….

Art affirms al that is best in man - hope, faith, love, beauty, prayer… What he dreams of and what he hopes for … When someone who doesn’t know how to swim is thrown into water, instinct tells his body what movements will save him. The artist, too, is driven by a kind of instinct, and his work furthers man’s search for what is eternal, transcendent, divine - often in spite of the sinfulness of the poet himself.

What is art? Is it good or evil? From God or from the devil? From man’s strength or from his weakness? Could it be a pledge of fellowship, an image of social harmony? Might that be its function? Like a declaration of love: the consciousness of our dependence on each other. A confession. An unconscious act that none the less reflects the true meaning of life - love and sacrifice.

Why, as we look back, do we see the path of human history punctuated by cataclysms and disasters? What really happened to those civilisations? why did they run out of breath, lack the will to live, lose their moral strength? Surely one cannot believe that it all happened simply from material shortages? Such a suggestion seems to me grotesque. Moreover I am convinced that we now find ourselves on the point of destroying another civilisation entirely as a result of failing to take account of the spiritual side of the historical process. We don’t want to admit to ourselves that many of the misfortunes besetting humanity are the result of our having become unforgivably, culpably, hopelessly materialistic.… Certainly each successive catastrophe is evidence that the civilisation in question was misconceived; and when man is forced to start all over again, it can only be because up till then he has had as his aim something other than spiritual perfection….

We all live in the world as we imagine it, as we create it. And so, instead of enjoying its benefits, we are the victims of its defects. Finally, I would enjoin the reader - confiding in him utterly - to believe that the one thing that mankind has ever created in a spirit of self-surrender is the artistic image. Perhaps the meaning of all human activity lies in artistic consciousness, in the pointless and selfless creative act? Perhaps our capacity to create is evidence that we ourselves were created in the image and likeness of God?

This is a good watch if you are curious to find out more about Tarkovsky’s films!

I’ve been a Tarkovsky fan since visiting an Orthodoxy Monastery in my late teens, the Monastery librarian had a copy of Andrei Rublev sitting out on a table and I immediately gravitated to it. I loved it but didn’t look further into the director as I assumed it was a one off film. Years later in a photo critique a photographer recommended Tarkovsky’s The Mirror when seeing my work and I’ve slowly digested his work since. Like you I’ve not watched everything he made waiting for the right moment when I can be fully present.

I certainly agree with “For the moment we are witnessing the decline of the spiritual” but also feel this decline has realigned Christianity towards its origins. Much of what we are seeing that is being lost has little depth and is often antithetical to the Christian story. The film Andrei Rublev does not paint a rosy picture of spirituality in the past either. Monks deal with jealousy, lords kill and maim mercilessly, there’s the ever present back drop of soldiers on horseback riding around doing their own cruelty in the name of Christ, and warlords ravage, rape and kill to such horrific extent that Rublev himself seems to lose faith and seems to question god by refusing to paint.

In the end it’s the desperation of the bell maker trying to save his own life, working tirelessly as a fraud and ultimately succeeding through his torment by divine accident that brings Rublev back to life and into grace from witnessing this miracle born of materialism and desperation rather than faith…. Or at least that’s what I remember of it. Thanks for the post. I’ve had The Sacrifice sitting waiting to be watched for a while. Maybe it’s now time.

Check out Mirror, if you haven't! I wrote a post on it with its Russian name, and it seemed to really resonate with people.