Dusty shoes along the Wayside

A shorty story of a pilgrim, and reflections on a recent commission of the Pensive Christ.

Let us imagine that an old clock has just chimed, ringing a resonate sound from 1,000 years ago. We sink back, dreamily and languidly to a mirage of roughly the year 1,000. There is a pilgrim who travels, to seek repentance, devotion and peace... The day is cold, the sky is colourless. His boils itch, snot runs from his nose, as he wipes it away on his crusty sleeve. He carries with him a woodcut print of St Christopher carrying Christ, it is stitched on the interior of his thick jacket, the pigment bleeds onto the linen cloth of his shirt whilst the sweat forms beads of prayer around it.

The ground of this land used to house monolithic slabs, casting shadows of an ancient wisdom, now at rest under the ruins of night. Yet a new monument has taken it’s place. A story of eastern mystery that fulfils the spirits and the shades of a forgotten civilisation, though they still murmur in the leaves, chuckling in the waters, they have barely evaporated under the mornings first rays of sunlight. In this landscape, there are saints, ghosts, angels and demons wafting around in their ethereal ways. The blessing and torment flows along him as the pilgrim goes on his way. Carried away through the draught, dark and narrow passages.

His dusty shoes are tearing open as his legs step one by one towards the sacred site. He passes a standing figure, carved in elm or oak. Its creaking splits and weather beaten age makes it hard to tell, this statue has seen many winters. It is his King mournfully seated...

Christ sits on the cold stone, the throne forged for him. This is no golden throne, at least not yet. Here he sits as the suffering servant. The stone is the altar table offering it's sacrifice, yet not by force, but by will. The figure seems to speak to him, “To you the victory! The day is won, death has been defeated by death.”

The lighthouse to the ships, pin drops in the eternal swelling ocean. He feels the weight of His sitting. In that moment an earthquake occurred, its tremors are still reverberating. The world is changed. In his wretched state he can’t see it yet, but he knows the Golden Blossom of divine grace has released it’s fragrance of paradise unto earth again… He drops to his knees and prays.

A carving of the Virgin Mary greets him next on his journey. The finest woman that was to ever grace this earth, the joy of all who sorrow, bearing unutterable beauty. Almond-shaped and almond-sweet eyes untouched by death, holding within them bottomless depth, the light of the sun fades when matched with the face of the Mother of God. The heart is warm seeing her, still as warm as the first spring days. Once known, no man would ever part with his Mother for the best mermaid in Christendom. We experience the utmost she does in colours. All her movements, all her graceful steps, deserve not half the glory she attains. It is something between walking and swimming. She has conquered enough by land, by sea and by air. The forests and the oceans gently sing her praises, the Queen of Heaven.

His destination draws near, and his shoes are now tatters of cloth. Before he falls from the discomforts and perils of the journey. The bells of the abbey ring a pearl to welcome him. A wafting melody of resonate bells, hovering like a cloud over the Abbey in a bird-sharp sound. The bells cease, and the creaking weight of oaken doors monumentally move aside. The echoes of carvings surround the space, in a dream of Eden in radiant tones of colour and stone. The chanting monks fill the air with a perpetual water-falling sound of song, it is partly the reason that the sun still rises each morning. The relic of a saint lays there singing to the flock for healing, and he begins to dance to the rhythm of the martyrs bones.

Forgive me for a slight indulgence of imagination, a romanticist amble of a pilgrim who may have seen carvings of the Pensive Christ as he goes on the journey to a shrine. Wayside markers, whether painted or sculpted are a very natural response to marking a land, far from passive markers of religious symbolism. It seems we just couldn’t shake off the druidic sense for large stones in a landscape. The faith in the Cross would bleed into the landscape, both spiritually and materially. It is like a tea bag being placed in a cup of hot water, where infusion takes place. They are there in one way to preserve the natural order; merely looking at one confirms the presence of God.

“The most important weapon to use against the devil is the Holy Cross, of which he is terrified.” (St. Porphyrios, Wounded by Love)

They are also waypoints for the pilgrim in their spiritual and physical journeys. This was a time when most people had more faith in Christ than in google maps. They were signs for The Way, dotted in hilltops, streams, crossroads and towns. “We did not always wander dejectedly in the wasteland of neon and soap operas.” the Sisters of St. Xenia Skete

These monuments and way points arose as one of many expressions from the baptism of pagan culture.

“The Church baptized pagan culture; the dross was scoured away and what remained was elevated. That baptized culture was Western culture. Wherever the Church went in Europe, She followed the same course. Whether in Ireland or in Gaul, in Britain or in Spain, She preserved all that was good and true in a people’s art and literature, nature and society. The pagan culture of pre-Christian Europe thus found in Christ the fulfilment of its highest longings, and Europe flowered.

For generations thence men and women poured out their deepest aspirations in building, singing, making, and living. They rejoiced in God, in the wonder of His works and world, and the legacy they left us sings of their joy. They built an age whose wonder and beauty we have nearly forgotten, where poetry ran quick in the blood and chastity was not shamefaced, but valiant, where mockery and baseness were not a sign of strength and tears were not a sign of weakness, a world of gentleness and courtesy, of honour and acuity, of nobility and integrity.” Quoted from the same article above by the sisters of St. Xenia Skete. (It is a truly brilliant article worth the read)

It is difficult to say for certain the numerous roles they would have played, but it is apparent they were like a foundation stone to the healthy functioning of a medieval town or village. I shall draw your attention to this brief but succinct article on the Wayside Cross in Medieval Europe. Very much recommended if this intrigues you. It delves into their role in art and architecture, social and judicial roles, pilgrimage, devotion and then their saddening decline and destruction. Here I am mournfully looking back at the Puritan’s wide brimmed hats and their wave of destruction again…

Reflecting on this, it appears that these markers were a visual and spiritually binding sacred force in a landscape, they of course weren’t the means of it to happen like some magic stone or idol, but signified and pinpointed a sacred centre within the landscapes of nations, a visual prayer, calling for our desire to return home. I came across a quote by Phillip Sherrard, which I think brings the point home. “Unless we can reinstate the sense of the sacred at the heart of all our activities, there can be no avoiding the cosmic catastrophe for which we are heading.”

It is a truly wonderful thing to have the landscape decorated with crosses, saints and the Theotokos along the Wayside. May this begin in Britain again. Of course in places like Romania, Lithuania and Poland this is still going strong.

Which is the reason for this post, as it is my second attempt at carving a relief of the Pensive Christ. Which has truly found it’s place in Lithuania, particularly with the Rūpintojėlis.

“As Christianity spread throughout Lithuania in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, so did images of Rūpintojėlis, as the wandering woodcarvers (dievdirbiai) of native folk culture carved him into hollowed-out tree trunks wherever they went. Today he is found not only at crossroads and in forests but in churches, homes, cemeteries, and shops.

Lithuanians relate the figure to their own passion as a people, especially since having had endured persecution under the Soviet regime, including mass deportations to Siberian labor camps and other remote parts of the Soviet Union in the 1940s and ’50s. About 60 percent of the roughly 130,000 Lithuanian deportees either died in the camps or were never able to return to their homeland—a tragedy still mourned by Lithuanians each year on June 14, the date of the first major deportation (in 1941), which they call the “Day of Sorrow.” Others were executed as political prisoners.

For these victims of repression, the Pensive Christ represents a God who identifies with the suffering of humanity. Perhaps he contemplates not only his own unjust treatment and death but also the countless injustices waged against others throughout time. And he weeps.” (Quote taken from an article here.)

Much of Europe has suffered tremendously, and continues to. The Pensive Christ shows the suffering, and the weight of it, without the gaudy graphic detail of horrendous torture. I don’t necessarily think we need to see the gasping horror of the whips lashes or the pouring blood to enlighten the depths of Christ’s crucifixion. It is the moment of stillness in-between the injustice, which the weight of it all sits. ‘O all ye that pass by the way, attend, and see if there be any sorrow like to my sorrow’ (Lamentations 1:12).

I’m going to use the quote I used in the previous post on the Pensive Christ, just because I think it is rather good at getting to this point.

“The seated Christ summarises the entire Passion; he has exhausted the violence, the ignominy, the bestiality of man… Here is the abyss of suffering, and the extreme limit of art … The seated Christ thinks and suffers. Thus, art had to express the profoundest moral suffering imaginable and link it with the extreme of physical suffering.” Émile Mâle

(Do go read the previous if you would like to hear more about the pose and the image)

It was an absolute delight to approach this image again through a recent commission.

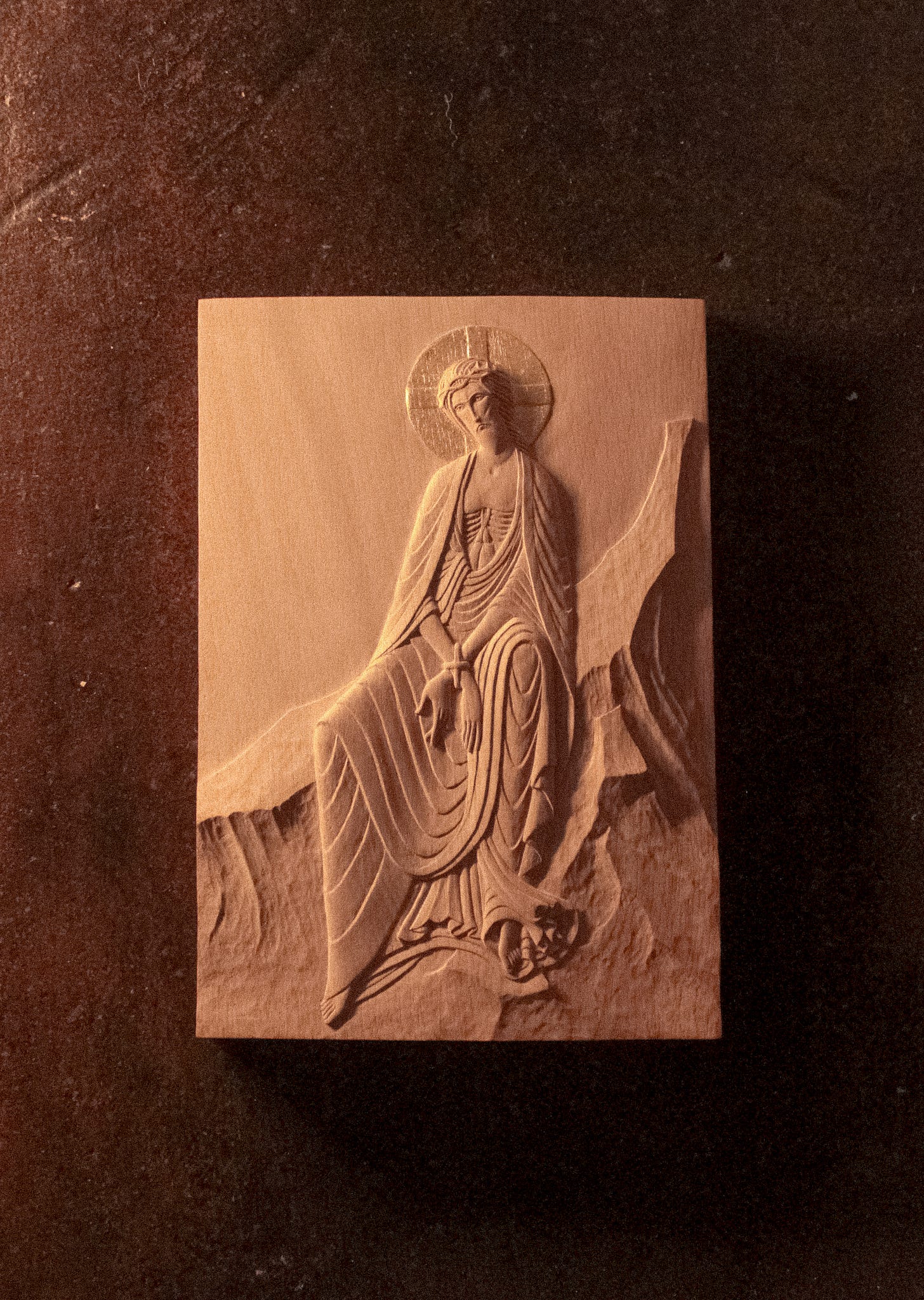

The recent commission, carved in oak:

This is a hybrid of sorts, trying to imbue the carving with wafts from Byzantium, to Northern European Folk, a slight hint to the English illuminated manuscript tradition and the sweeping lines of the Romanesque.

The images of Christ the Bridegroom and The Pensive Christ, appear as a pictorial refinement of the Suffering Servant. It seems to reflect the Creator’s tears, the melancholy can’t be escaped. It is the build up to the echoing of Christ’s cry “My God, My God, Why hast thou forsaken me?”. Talk about a headscratcher…. One of the many words Christ spoke that sent a pulse to perplex and reverberate for 2000 years and onwards. It is a mystery, it is profound and disturbing. How can we attempt to explain the things that Christ says and does! We sit with this and know it cuts somewhere deep.

I have been reading Wounded by Love by St. Porphyrios, which I am in complete awe at. I read this which I thought be appropriate to include as a finishing note.

“As I heard the Gospel reading I was deeply affected. This happened because I saw the image before me, of Christ himself. One Good Friday we were doing the service. The church was packed with people. I was reading the Gospel, and when I came to the phrase, Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani, that is, ‘My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?’ I was overcome with emotion. My voice broke. In front of me I saw the whole tragic scene. I saw that face. I heard that voice. I saw Christ so vividly. The people in church waited. I said nothing. I was unable to continue. I left the Gospel on the reading stand and turned back to the sanctuary. I made the sign of the cross and kissed the Holy Table. I brought to my mind another image, a better one. No, not a better one. There was no more beautiful image than that one, but the image of the Resurrection came to my mind. At once I calmed down. Then I returned to the Holy Doors and said:

‘Excuse me my children, I got carried away.’

Then I picked up the Gospel Book and read the passage from the beginning. But at that moment the whole congregation was moved to tears. That was bad. A person may think what he will. But it is not good to allow ourselves to be carried away. We need to be restrained.”

“I don’t necessarily think we need to see the gasping horror of the whips lashes or the pouring blood to enlighten the depths of Christ’s crucifixion. It is the moment of stillness in-between the injustice, which the weight of it all sits. ‘O all ye that pass by the way, attend, and see if there be any sorrow like to my sorrow’ (Lamentations 1:12).” Amen!

The weight of what Christ has endured and accomplished on our behalf, this is what I meditate on in my pilgrim’s journey when I encounter the Pensive Christ and what I see in your carved icon Ewan. It encourages my own stillness on the Way, despite worldly tensions, but always with eternity in view, the eternity God has won for us! In the Pensive Christ carving, when light hits from Christ’s right, it reveals our hope that rises in the East, an eternal hope and joy cast on our temporal struggles and sorrows. We journey on and homeward!

Peace and thank you truly Ewan for sharing your gifts and these thoughts and considerations on pilgrimage and Pensive Christ.

Your new piece is stunning; a great success in combining the different artistic strains. What a beautiful doorway to contemplation! Thank you for sharing it.