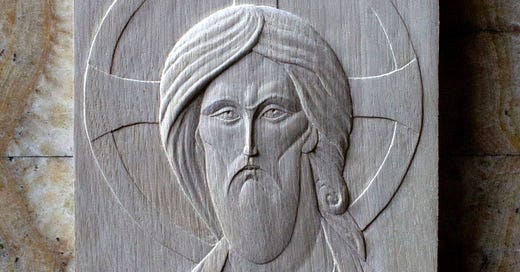

Christ after Rublev

A commission with a medley of musings on Rublev, Wabi-Sabi and Medieval Gardens.

I was very grateful to receive a commission for this icon of Christ as Saviour. It allowed for a second attempt at an image I love so dearly. And that is Christ the Saviour by Rublev. As I have mentioned before, St. Andrei Rublev has been foundational to my approach to the Orthodox world. Years ago, I found the white walls of an evangelical church cold, there is an air of piety and devotion, a biblical zeal which I admire, but sitting there…. One thinks of a colourless evening after a rainy day. Appearing a little too flat, tasteless, like a fillet of boiled plaice. I think any spiritual path that denies or doesn’t make an effort with beauty, or with the Mother of God is missing something crucial.

Below shows the first attempt, created before this substack was started. This piece was made as a response to Rublev. An attempt to enter into iconography. In the Orthodox view, icons are many things but I kept hearing they are windows into the realm of God, a view into heaven. Now what does this mean? Is that to say it is what heaven will look like? Or what Heaven already is? I suppose this is part of their mystery. They are invitations of sorts, just like St. Andrei Rublev invited me to enter into something eternal, or at least ponder upon it. With Rublev it was an experience of something getting into my insides, and I was swept away by currents I can’t see. This was the start, my training was in carving and clay. To carve icons felt like a very natural response, though I wrestled with thoughts and doubts. I still do. But I couldn’t help but hit the chisel with the mallet to try to understand. I think the creative mind, which we all have in varying aptitudes, needs an output. The mind races with thoughts and theories. To act seems to be the key.

Both attempts I feel I have still yet to capture something that Rublev’s offers. Perhaps it can’t be transcribed to relief, its majesty is within the medium of paint. Most likely its because I am not there yet in skill or spirit, Rublev is a saint after all!

There is a lot in this image. The gaze of Christ is the initial draw, the incompleteness of it is very much part of its charm. The beauty isn’t taken away by the impact of time. It’s a miracle if anything that the face of Christ has been left untouched, particularly His gaze. And it is also a miracle that it was rediscovered, alongside St Paul and the Archangel Michael found in 1918 under a pile of firewood in a barn near Zvenigorod. A mysterious story indeed.

We have in this work a fragment of a masterful work that appeared from the fogs of time. A purist may say this icon has been ruined. But on the contrary, I feel it has been slowly renewed in its fragmentary nature. Time has played its part in the mystery. There is this sense of unknowing to it, what once formed the whole picture is now gone. Which perhaps mirrors something of the journey to know Christ. Christ can sometimes appear vague, confusing and not fully clarified, mystifying. In a way, this is how an eternal truth should appear to us, as a fragmentary glimmer to the great depths of the infinite. How else could we approach something so vast? This icon appears as a message in a bottle that has been washed ashore from that eternal ocean. This is a bright pair of eyes, that looks at us, and makes the darkness within unsure. He appears as this mysterious stranger who has His eyes locked onto us, and in the panic of this realisation we look away pretending we never saw His gaze. But we look back and the gaze is still there, and we can’t stop looking at it. To slowly realise this is no stranger, you know this face. He draws you in, confirming that something you could only dream and hope for is true, bringing a comfort beyond words. But a strange comfort both beautiful and terrifying all at once. “Who can hide from the fire that never rests?” - Heraclitus

It has a very eastern feel to it, and not just Russian. The process of its aging and damage has very much become part of the icon itself. Akin to an old English stone cottage where the moss is as integral to the stone. This image has within it an element of wabi-sabi, the aspect of times passing touch is very much part of it’s allure, but also the powerfully simple and gracefully elegant gaze of Christ, you can return to again and again. I know the term wabi-sabi has become a bit cliché, but there is a tenderness to this idea. I am someone who has a strange magnetic pull towards Japan, I think the internet term is a weeaboo, though I wouldn’t say I go that far… (I am not that fond of anime!) It’s more in the practicalities and their craft. I use Japanese wood carving chisels, my interior spaces attempt to reflect their certain finesse, and I drive a wonderfully analogue Honda Civic MB from the year 2000. Japanese cars from the 90s - early noughties are unmatched when it comes to reliability! But that is a whole discussion for another substack.

I should note that I have never been to Japan nor do I know a great deal about it. My experience of that culture comes mostly from aesthetics and imagination, ceramics, prints, using chisels and driving an old Honda. I did read a good introductory book on Wabi-Sabi, titled “Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers.” by Leonard Koren. From my understanding, it is clear why beauty was fundamentally prevalent before Japan’s modernisation. Within the realm of wabi-sabi, it is good for communicating subtlety of mood, vagueness, and the logic of the heart. A thread that connects a similar essence to the Orthodox way, the vagueness of embracing a mystery, and the reunification of the heart and the mind in the nous, and through that act, finding a means of expression through a lived life.

Wabi-Sabi was of course born out of spiritual discipline, being more of a way of life than an art style. This lofty term is a small way of trying to express something seeping out of Zen Buddhism, something I have never really been that interested in or looked into. But I do think all truth is God’s truth, and there are things we can gleam from all teachings, not in an ecumenical way of saying it is all the same. That seems absurd to me, but engaging with the variety of a cultures means of expressed thought and aesthetic knowledge.

“ ‘Wabi’ originally meant the misery of living alone in nature, away from society, and suggested a discouraged, dispirited, cheerless emotional state.” (From Wabi-Sabi, for artists, designers, poets & philosophers) Now this to me sounds like a hermit without Christ! Or most people lost in the digital desert come to think of it… But regardless, it points to the birth of something from the hermit and ascetics, in which much of Christian and many other histories seem to be found upon. Hermits and poetry, finding meaning from simplicity, insights into the unseen connective tissue that binds. It points to an experience in which a religion is built around. With the hermit, it is very much one of a person seeking solitude to be with God. The great gust from elsewhere fills the lungs and bones, the enthusiasm erupts. The mask is stripped away, the veil is lifted and the sacred man is revealed. The person you are when you fall into the hands of the living God, stripped from all of those comforting and signifying moments of identity and pride. “It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the Living God. “ (Hebrews 10:31) It enters a person into something eternally youthful and ancient all at once, both beautiful and terrifying. At least these are musings of a hermit… I may be entirely wrong. As I am not one.

Perhaps the best way to reflect the mood of Wabi-Sabi is by reading a Haiku.

“All around, no flowers in bloom

Nor maple leaves in glare,

A solitary fisherman’s hut alone,

On the twilight shore,

Of this Autumn eve.” Fujiwara no Teika (1162 - 1241)

It is beautifully melancholic. A striking image of simplicity. Which is a key. This is a state of grace, entered into by a heart lead intelligence, sober and modest in it’s restraints without removing the poetry.

Wabi-Sabi found an expression in the love of tea and the tea ceremony (and gardens). As a Brit, tea and gardens I am drawn to naturally! A Zen priest saw the opulence coming into the tea ceremony. As a response to this he introduced simple, rough, wooden and clay instruments to replace the gold, jade, and porcelain of the Chinese style tea service that was popular at the time. This was a very bold move and a dig, but an important step pointing towards restraint. The tea master Sen no Rikyū (千利休, 1522 – April 21, 1591) introduced the wabi-sabi ideals to the royalty with his design of the teahouse. "He constructed a teahouse with a door so low that even the emperor would have to bow in order to enter, reminding everyone of the importance of humility before tradition, mystery, and spirit.”

This I do like. There is a truth here, and an asceticism. It is humbling, and an active response to grandeur and fleeting ornamentation for the sake of ornamentation. I think these principles can be applied to a Christian aesthetic. It is a restraint, and one knowing that not everywhere has to be like Hagia Sophia, though I don’t wish to undermine the importance and need for buildings like the Hagia Sophia, or the great Cathedrals of Europe. I think this will be more directed to what us the lay people can manage in our homes or smaller communities. It is a form of asceticism expressed in the aesthetic. Beauty can be found or nurtured with the simplest of means.

New things come into being so fast these days, many technologies and thoughts are replaced and cast aside at lightening speeds. It seems some things don’t have much time to dwell, only for many to focus on the new. There is no horizon to stand on to see these changes clearly, as the sight in view has already shifted by the time we spot it. While we stand looking there is no time to shape a memory before something else has barged its way into view. This is why I am intrigued to find a Christian aesthetic inspired by the ascetics. I think it is a response or a retreat from the profane, the amassing clutter and lunacy of speed. Some kind of denial to the decadence and over-stimulating nature of today is needed for the soul to breath. And that is to strip away. There is a fine balance to find its orchestration, to recognise the pleasure we get from things, and the pleasure we get from the freedom away from things. This seems very wise to me. It is a refined measure of tending the weeds in a garden.

A simple rule from Benedictine order. “He will regard all utensils and goods of the monastery as sacred vessels of the altar, aware that nothing is to be neglected” This rule is quickly forgotten the moment we step into Ikea or a supermarket, where the radiance of an object is dissipated in a sea of plastic and formica. The rule makes me think of the wonderful words of ‘God being “Present in all places and filling all things.”. This being true, it would extend to our means of living and the way we use objects as extensions of a sacramental, liturgical living. This isn’t to say a laptop is to become a holy object, or a sponge is now akin to the chalice that serves the Eucharist. But more so where do these objects and spaces lead us to… Where do they take us in our wondering? What or who do they serve?

Though we may not be in a monastery, we have our homes and our families. It is hard to transform these moments, as it is so easy to fall into what we know. Habits, rituals and repetition can be golden or disastrous. Can these be affected by beauty, by a change of mind? Which is probably both at the same time.

If we look at this tea house as an example, they are no royal palace but incredibly subdued, there is a spiritual quality radiating from them. More often than not there is always a garden tied to the house. They are akin in some regard to monastic gardens, cloisters and roses, herbs and water, the green lungs to the monastery. A balance of nature and man.

The image of a garden in the monastery during the Middle Ages was not purely for admiring nature. Integral to the Medieval universe, a vision in which God is at its very centre. A mindset where the material things weren’t in themselves of importance, but of the spiritual realities they refer to. The garden is an enclosed space, it is the place where the story of man began and the story shall end in order to begin, the world of paradise, in God’s pocket. Now it is lost with some remains, and our hearts yearn for it. Culture and civilisations to me seems like a continual search for that lost paradise, however distorted.

The organisation of the monastic garden, especially of the isolated monastery took shape as autonomous and self-sufficient running, it was modelled on the two concepts of Desertum and Hortus conclusus, one being a wasteland and the other being the enclosed space. Linking both the hermit and the community: these two aspects merge into a harmonious balance, it seems a necessary part of culture, as a lot of the Hermit Saints are always drawn back into culture, into the community to guide. Silva refers to desertum-hortus as nature-culture. The hermit is forged from the wild natural environment, alongside that of the cultivated countryside:

“They cultivated the land and made a number of uncultivated sites healthy and fertile. The deserts resounded not only with their prayers, but also with the clatter of the axes. Worried about advantageous projects, sufficiently educated, full of strength, fervour and perseverance, they managed to accomplish quite extraordinary works by themselves, spreading new lights, interesting practices to all branches of agriculture, and achieving fruitful results.”

Silva Ercole, Dell’arte dei giardini Inglesi, 1801

One such hermit is St Fiacre of Breuil, often represented with a spade and a Gospel.

He was a 6th century Irish monk, hermit and gardener, priest and abbot. Perhaps Paul will write of this Wild Saint one day… But the story goes… He was trained in a monastery near County Kilkenny, and then went on to become a hermit, he was a very popular hermit, being swamped by visitors, a contradiction of sorts… He yearned for solitude, and fled to France. He ended up at Meaux a small town to the north-east of Paris. The local bishop, Faro, had Irish connections and is supposed to have offered Fiacre all the land he could turn over in a day. Fiacre, didn’t use a spade or a plough, but prayer and a hermits staff.

This raised a few local eyebrows, and one disbelieving woman, rushed to the bishop telling him what Fiacre was doing, proclaiming the devil is at work. Faro immediately set off to see for himself but immediately saw that Fiacre’s wonder-working was a miracle from God.

Having built a hut and created a garden to grow his own food Fiacre lived a life of manual labour, combined with prayer, vigil and fasting. Once again his name spread and, just as in Ireland, he was soon swamped with visitors and even a group of disciples. This time however Fiacre did not run away from the crowds but instead built a hospice for travellers, and a shrine to the Virgin Mary where they could worship. Gradually this developed into the little village of St Fiacre-sur-Marne.

“He marks the ground and it is covered with plants, sits on a stone and that becomes a Cathedral.” This is so very brilliant. This sets the stage well for the stewardship bestowed upon us. And truly captures that holiness brings life, draws it in to transform and sustain it.

So what does wabi-sabi, monasteries and gardens have to do with this depiction of Christ? I don’t really know, I went off on a bit of a tangent and got lost in reading about medieval gardening. Suffice to say, the connections are definitely there. Perhaps one day, this carving will appear in an old barn, full of wood worm, charred at the edges. But the gaze of Christ will still survive to look into the souls of those who pick it up.

A short video I made a while back you may enjoy showing the progress of the carving of the first attempt at this icon.

I found a wabi-sabi face to Christianity when I was living in the Republic of Georgia. In the countryside I often came across ruined stone churches and shrines, some reportedly as old as the fourth century, where a local tenderly left icons and stubs of wax.

Ewan your pondering on Wabi-Sabi, tea rooms and gardens reminds me a bit from a chapter on "Work" from a true treasure of a book titled, "The Secret Seminary" by Fr. Brendan Pelphrey. He states, "It is important to realize, finally, that the object of work that we perform as prayer, is not to improve upon nature but to import nature, as it were, into the surroundings of human beings who have lost touch with creation itself." He's speaking to our work against chaos which "is the practical manifestation of evil" as a small recovery of order (goodness, beauty and truth).

The chapter concludes thus, "Finally, the theologian of the Desert does not need to live in any particular place or neighborhood or surrounding. Rather, a dialogue springs up with whatever surroundings he or she inhabits, perhaps through obedience to a bishop or a church. Moving about freely, students may find themselves in the countryside or in the midst of urban blight. Wherever they are, their task is to make their surroundings bloom, to create peaceful spaces where others may come and rest."

Maybe a bit of Paul's references to "cooked" and "raw barbarians" here as we work and pray in various places where we are called in purposeful ways to be planted, the places we "build our huts" both physically and spiritually. Peace.