Cherubim, Carving an Angel

A recent commission, with thoughts exploring the influence of the Romanesque and the medieval, the modern era of art, and a pondering on the importance of beauty. (And a carving process video)

As I sit to write this piece on the commission, I ponder where to start. It is quite difficult to describe the creative process. Perhaps a good place to start is to show the influences. We would be nowhere without the masters that came before.

After viewing these, I hope you can see how they have fed into this new carving (shown below). The wheel has already been invented, and there is a great respect for the masters and their traditions. When developing an idea, I always turn to the picture books, it is a way to warm up, stretching the muscles so to speak, and so begins the hunt for beauty.

The Old

When it comes to carving, I am always drawn back to the Romanesque Period. I don’t know if it’s a vastly long distanced heritage calling, or something else entirely, but I am oh so fond of it. A lot of ink has been spilled over the question of it’s beginning and end. The seed started sprouting during the Carolingian period (Roughly c.751 - 987) guided by Charlemagne. It didn’t happen as a sudden rupture from one period to another, but gradual shifts giving life to different forms, with similarities that links the works together. The varying styles all intermingle and flow from one another, the pilgrimage and travelling craftsmen would of enabled people to come to and thro, travelling vast distances and bringing back new spiritual learning and a transferal of technique. Making it an international and very local period. Symbolically this was the time of stone pillars and the laying of foundations. The echoing tap of chisel and mallet hitting stone was probably heard as often as bird song.

The Romanesque period lasted roughly from around 1000-1200, a short time to build churches. It was an absolute explosion of creative force. Imagine the radius of an atom bomb reaching Britain, Germany, France, Spain and Italy, rather than levelling the ground in destruction it was raised up in creative fervour. A part of this boom was due to monasteries and pilgrimage. I will of course point to Eugene Vodalazkhin’s book Laurus if you wish to be engulfed in the world of a pilgrim.

You would think the name Romanesque would place it as a direct descendent from Roman classicism. Partly this is true, it was a new style emerging from the ruins of the old empire, influence did come from Roman technique, yet stylistically it was adapting a new expression altogether, an attempt to take in and adapt Byzantine and Roman works, developing a fine-tuned European expression. The word ‘Romanesque’ was born in the 19th century, it was a description like the word ‘Gothic or ‘Baroque’, to disparage the style it named. This was when we had a vigoured imagination for classicism, Roman imperialism and Empire, in which it viewed these ancient works as debased forms of that much grander, even older, Greco-Roman classicism. When looking at the sculptural elements, with this higher regard for realism, comparing that standard to Medieval works makes the Romanesque appear crude or quaint, perfectly sweet but not quite great, kind of Roman, but falling short. As you can probably tell, I certainly disagree!

The aim for the Romanesque carver was on holy rather than objective realism, an emphasis on the sacred and the eternal rather than the realistic, reflecting a spiritual depth raising it above natural realism. Realism can suffer greatly from striving for perfection, it clings too close to a life-like impression, which of course, can never be captured in image. Visually, classicism is very impressive, the skill is tremendous, and the techniques shouldn’t be disregarded, the methods of classical drawing and sculpting can train the eye and mind to really observe your subject. Yet the chains of realism doesn’t allow much room to enter into the poetical expression, which goes beyond factual objectivism, expanding in elements of abstraction, entering into the mystery. The Byzantine tradition flowing into Europe and the Rus was one of a ‘spiritual perspective’, an internal truth, seen with the nous, focussing directly on what is of most importance. Compared to a ‘realistic perspective’, an external truth, focusing on the material world and slavishly trying to imitate that in mastery. In the example below, how else could you realistically and naturally portray Christ saving souls from hell whilst trampling on death?

The Romanesque was nurtured in a time where the liturgy and Byzantine traditions gave insight to furnish material for the talents of stone-carvers. Illuminated manuscripts and metal works would trickle down into the font of the carvers imagination to have an affect on the carving of the stone bibles adorning the churches and cathedrals across Europe. What I love most about it is the transformative nature of the style. The solid immobility of stone is transformed into a rich dynamistic grace. There is an elevation of the subject in powerful simplicity. The Romanesque sculpture grows subtle gestures and ornamentation. The carvings become marked rhythms with a fine pointed eloquence. Drapery is no longer a fabric that rests on a person, but pulses across the body, as if the spirit has come alive in the fabric carved in an exquisite rapture of movement. There is a wonderful tension between the static and the fluid, which I see as a truly marvellous accomplishment of the Romanesque.

The impression this art has upon many is clear, it points to awe, wonder and worship. The heart leaps responsively upon looking at it. Lessing in his “Laocoon”, says, ‘Beauty is best conveyed not by itemizing the finer points of the beloved or the features of the landscape, but by showing the impression it makes on the those who look at it; the same may be true of holiness.’

The carvings radiate a kind of force that draws you in. It’s power lies not in appearance but emotions, yet under control emotion, with limitations, not falling into over sentimentalising. It portrays an eternal simplicity which holds gravity and poignancy, depicting teachings and stories from scripture. Medieval man and woman by us today may be viewed as naïve. Yet there is a great deal to learn from them, simplification over indulgent decadence, beauty and grace over vulgarity and coldness. I imagine this to be a time where Faith existed in every act of communication. A perception of life where God is seen in every corner, an undeniable longing for the ideal, for absolute truth. From all angles, this faith was expressed and passed onto to one another, directly and indirectly, whether you knew it or not. The subject for the artist existed within, and it demanded expression. It was a spiritual endeavour to create these works, aspiring to make man more perfect, more like Christ. The production of these works were an act of love, copious years of toil transfigured rough stone to marked beauty. It condenses into an image of the world that captivates us in its thought, restraint and nobility, coalescing into harmony, becoming a wonderful expression of faith through beauty.

Andrei Tarkovsky, the great director captures the creative act so eloquently in his book Sculpting in Time. “An artistic discovery occurs each time as a new and unique image of the world, a hieroglyphic of absolute truth. It appears as a revelation, as a momentary, passionate wish to grasp intuitively and at a stroke all the laws of this world–its beauty and ugliness, its compassion and cruelty, its infinity and its limitations. The artist expresses these things by creating the image, sui generis detector of the absolute. Through the image is sustained an awareness of the infinite: the eternal within the finite, the spiritual within matter, the limitless given form.” Art in all it’s forms impacts the soul, and it shapes our spiritual structure, both positively and negatively.

I do wish to note that I am fallible to paint perhaps too picturesque a picture here of the medieval… Of course it wasn’t all sunshine and roses back then, but I reckon it wasn’t so dark as the narrative would want us to believe, look at what they created. This is more about learning from them, particularly when it comes to the creative act. We can only gaze at the fragments left behind to build an image in our mind of what this civilisation would have been like. We shall never truly know. But their air still lives on in these carvings and in the landscape, and though completed 1,000 or so years ago, they are still alive for us today. Much like the teachings of the Desert Fathers.

I suppose I have made the case for my aims in carving! All art is a continuation of what came before, we can’t escape our ancestors. A vast span of time separates myself from the carvers of yonder year, yet I hope I can come close to capturing what they were able to. I love carving, and this will take a lifetime to build upon, and even then I most likely won’t be able to come close. I know it is easy to fall into imitation and become derivative. Particularly when it comes to iconography, it can all too often become schematic, and in a way false. A pastiche of the past becoming stale, not being endued with the freshness of the present. I don’t know how best to do this, but we have to start somewhere!

The Modern

Another area of influence is early 20th Century Modern art, in some ways this was the beginning of a return to find that poetic, abstract and sacred language in works of art again. New ideals were being found outside all the Greco-Roman classicalism, all manor of isms started emerging from the arts. It was even a basis for iconography to return back to it’s more ancient traditions.

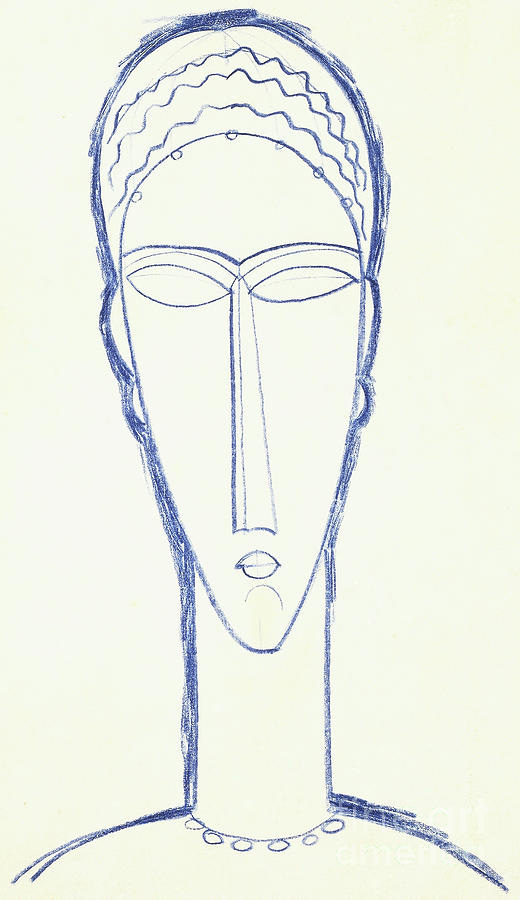

One artists work I admire is Modigliani’s carvings, they have always intrigued me, there is something quite alien about them, and by alien I mean foreign or unknown. Though Modigliani and the Medieval artist existed in a vastly different time, I think the connection is simplification and purification of forms. His sculptures melded the influence of African sculpture with strains of Egyptian, Cycladic, Greek, Romanesque, and Gothic styles. An important leap to be made in the world of art, bringing it back to something a bit more wild and less pomp. Which has lead to various paths for artists today, some good paths and some bad paths.

Since the Renaissance, the unknown craftsman has shifted to a substantially individualistic, more bohemian character, with the ‘A’rtist gradually being born. Giorgio Vasari, was one of the first to recount the lives of these new, individual artists, he presented them as these secular kind of saints of flowing genius. Since then, it was heightened even more so by the Romantics of the 18th and 19th century, in which the podiums grew even taller for the elevated life of an artist rather than just a craftsman.

I do think we put far too much on the role of the artist, this is something I wrestle with the idea of, I flitter between seeing it as a deeply spiritual act, and just work to get done. I suppose it is both. I see it as the same call that everyone may come to answer, knowing how to do God’s work, in your capacity.

One aspect of the shift of the craftsman to the artist is that they started to exist on the edges, poking and prodding at societal norms, which can be good and bad, either bringing about reformation or revolution, growth or decay. I suppose I was once semi-bohemian having shouldered length hair and burgundy velvet trousers, to my own embarrassment, perhaps it is a rite of passage for creatives today, particularly in the arts, you enter the outskirts, and either get stuck in the drudgery of self-loathing thought and expression, or come out the other end hunting and desiring beauty, seeking the ideal and wishing to use your gifts for good.

It is all too easy to slander modern art today, there is some of it I do admire. But from looking at the vast array of contemporary art it seems to me that it has gradually lost it’s sights on the search for the love of moral beauty, the alluring aspect of art is not vital. For much of the arts has been overcome by the desire to affirm the value of the ego and individual expression for it’s own sake. There is little harmony to be found. It becomes an eccentric, marginal activity for those who believe the reasons for making art has it’s value as simply a display of the self.

The seeds of this individualism found it’s soil in the times of the Renaissance. One story that exemplifies this is of the “divine Michelangelo” and the story of the installation of his Pietà found in Visari’s ‘Lives’, Michelangelo overheard someone remark that Cristoforo Solari did such a tremendous job here! Outraged by this, Michelangelo carved the words on the sash running across Mary's chest.

MICHÆLANGELVS BONAROTVS FLORENTINVS FACIEBAT

("Michelangelo Buonarroti, the Florentine made this")

Now the voice of the self wanted to be known, pride arose, and it is very easy to fall into. And today even more so, thousands upon thousands of voices are all screaming to be heard and desire admiration, there is no room for a unifying principle when every artist wants their own podium to stand on.

I don’t think individualism is a bad thing, it is part of the joys in creation and mankind, distinctness and variety. But this extreme form of individualism leads to harrowing fragmentation and isolation, chipping away at the foundations of tradition. The fragmentation is nothing new, it’s like a plate that has been smashed over and over again, leaving thousands of pieces to put back together. Which will be a monumental task to do, and a duty to fulfil. Alexander Blok said that “The poet creates harmony out of chaos.” Not all of us are able to write poetry but we can all act and participate in a creative life rather than a destructive one. I shall add to this the wise words of St Porphyrios “For a person to become a Christian, he must have a poetic soul. He must become a poet. Christ does not wish insensitive souls in his company. Poetic hearts embrace love and sense it deeply.”

I believe the creative act is at its core, the attempt to mirror the reality of heaven, to rise above the profane. By creative act I don’t just mean painting a picture, but in all our actions. Beauty encompasses much more than just a painting, a painting is just one small part of it. True beauty points to the higher state we are made to exist in, it goes beyond the corruption, and it is alluring. The creative act in life reaches upwards to bring down small nuggets of the truth and reality of the kingdom of heaven. This can be expressed in all action, from how you lay the table and offer hospitality, handing a loaf of bread to the person living on the street and so much more. Each new act of beauty is one new thread woven to close the gap of separation we feel from God. It is a returning to ourselves and in that return, we are like the prodigal son returning to Christ, who’s love has never nor will ever leave us, despite our ignorance. The mirror or the reflections of ourselves can be cleaned and we can start to see Christ in us and in others. This is something I am painfully and slowly realising. We are starving for the radiant and the eternal kingdom. And this starving needs nourishment, which comes in the form of beauty, in all it’s manifestations.

“The mind feeds the soul, and whatever good or bad things it sees or hears it passes on to the heart, which is the center of the spiritual and physical powers of man.”

Elder Joseph the Hesychast

To live a creative life we must bathe in the healing baths of beauty. The essence of beauty is intrinsically interwoven with how we are to flourish as stewards, it is a form of love and healing. It is of a great shame that we have grown accustom to brutality, I know I certainly have. The profane and vulgar have become the norms of many operations. This system/culture of vulgarity seems to me an act of aggression on mankind’s dignity and nobleness, step by step, inch by inch, we have gradually succumbed to the inferior, to the debasement of beauty. It creeps in and we slowly cease to feel the need for the beautiful or the spiritual, continually consuming cud. Which seems like a form of neglect, Elder Joseph the Hesychast has some further wise words on this.

“Neglect plots against us. It’s like a drought that hinders any kind of planting. It hurts everyone. It hinders those who want to begin the spiritual battle and stops those who have begun it. It hinders those who are unaware and keeps those who have been deluded from returning.”

The unseen evil is expressed in action and in material, tormenting us as it grows and is built, the profane attacks the sacred. I think it’s only when the soul is shaken, and awoken to beauty that is summoning us continually, that the cold, vulgarity starts to leave distaste, a horror on the eyes and on the soul. The veil of the profane is lifted, the space becomes pregnant with sacredness, a wholly new light not seen before is coming into view. It seems to me, akin to a form of repentance, repentance used in the Greek meaning of the word ‘metanoia’, meaning ‘a change of mind’, a reversal of our habitual ways.

True beauty demands love, it is a calling of sorts. There is a reason why beauty stops us in our tracks, a slap in the face if you will, a wake up call, it is an invitation to the participation of uncreated light, and thus of healing. There is a beauty which is translucent and guides you towards the source. In this sense, beauty is also discovery. In the discovery of beauty the contrast of what was once a daily reality and normality almost becomes an attack on the soul, as if a dull weapon is whacking the eyes and the heart. The profane is a spell cast upon us, calling us to chase phantoms and worship idols, closing our eyes to the utmost, purest of beauty and ultimately of love, which has been given unto us as a miracle.

I shall use the masterpiece by Hieronymus Bosh to help illustrate this point of beauty degrading due to our capacity to indulge the profane. There is an attack on the soul and the spirit, the revelling becomes the torment, pain and pleasure become confused. The chaotic designs that we choose becomes a prison in which we lock our own doors and our devoured. It is true horror. Systems upon systems are pushed onto us to dehumanize and and desecrate the nobility of personhood, and take us away from paradise with Christ.

Anyhow… Back to the piece!

When it comes to making artwork, I think having an open mind is important, but not too open! Finding the connections of Modigliani and the Medieval can be found, it is evident in their work, less evident in their lifestyle. With the face in this carving, it was a bridging of Modigliani and Byzantine iconography, seeing the connection to both and linking them. Hopefully achieving a balancing act of retaining the blessed limitations of previous forms and tradition, and not getting too lost in the terrifyingly excessive freedom promised by the current state of affairs, which is no freedom at all.

Here is a short video showing the gradual creation of the carving:

Absolutely lovely. Thank you so much for your thoughts!

Beautiful!