Each art has its own poetic purpose and meaning. The different ways of expressing truth has a particular role. These things come into being in order to express an area of life, art forms are born from a meaning which had yet to find a voice. I think all art forms emerge from a spiritual need, being windows to the spiritual state of the epochs. The woodblock was born to create multiple impressions of the same image, it is a reproduction technique and the forerunner to the industrial process of printing. The process and material dictates the image. The woodcut allows linear graphic qualities whilst also being coloured. I think due to the limitations of woodcut there is a simplicity that needs to be achieved for a successful work. It requires the co-ordination of multiple crafts and a lot of human effort, the multiplication of one image is suited for the masses. It was first born for religious purposes then grew as an urban and commercial phenomenon, it emerged to suit the populations in busying and growing towns. Which is good and bad I suppose, it all depends on what messages are trying to get across. Most prints in history have been relatively simple, being the cheapest option for image making, it only requires a block and surface. With this simplicity of creation, it is a quick way to respond to the tastes and needs of the time, whilst being able to reach many people. The woodblock has served a wide range of mostly utilitarian purposes in the past: Religious means, Advertising, decoration, education, entertainment, information, political propaganda and titillation. Within these expressions of the print, a wide range of themes could be shown.

The woodcut is the oldest method of printmaking. It is primitive in material and old-fashioned in technique. The book was born from it. It’s origins were in surface design and publishing, the earliest use of using carved wood for surface decoration can be traced back to the Han Dynasty(202BCE - 220AD). In this period it was primarily for creating radiant and repeated patterns for lavish textiles, fine woven shimmering silks adorned with rippling pattern. The woodcut moved it’s way to paper as that was also being developed. One of the oldest fragments of paper found was in around the very early Han Dynasty, where it was used for careful wrapping for delicate objects, It was in the year 100AD that a eunuch named Cai Lun invented paper for writing, creating a surface much more refined.

It was during the Tang period (618AD - 907AD) paper and printing took off like a kite, texts were carved in wood and so were images, in this time not only were books invented but so was ice-cream. They found many uses for paper, being the newspaper, money, napkins, paper cups, tea bags, envelopes, kites, windows, lanterns and even toilet paper (Gone were the days of the sponge on a stick!). I find it amusing to imagine a Chinese fellow from the year 700 eating an ice cream, and whipping his mouth with a paper napkin. Nothing is new under the sun…

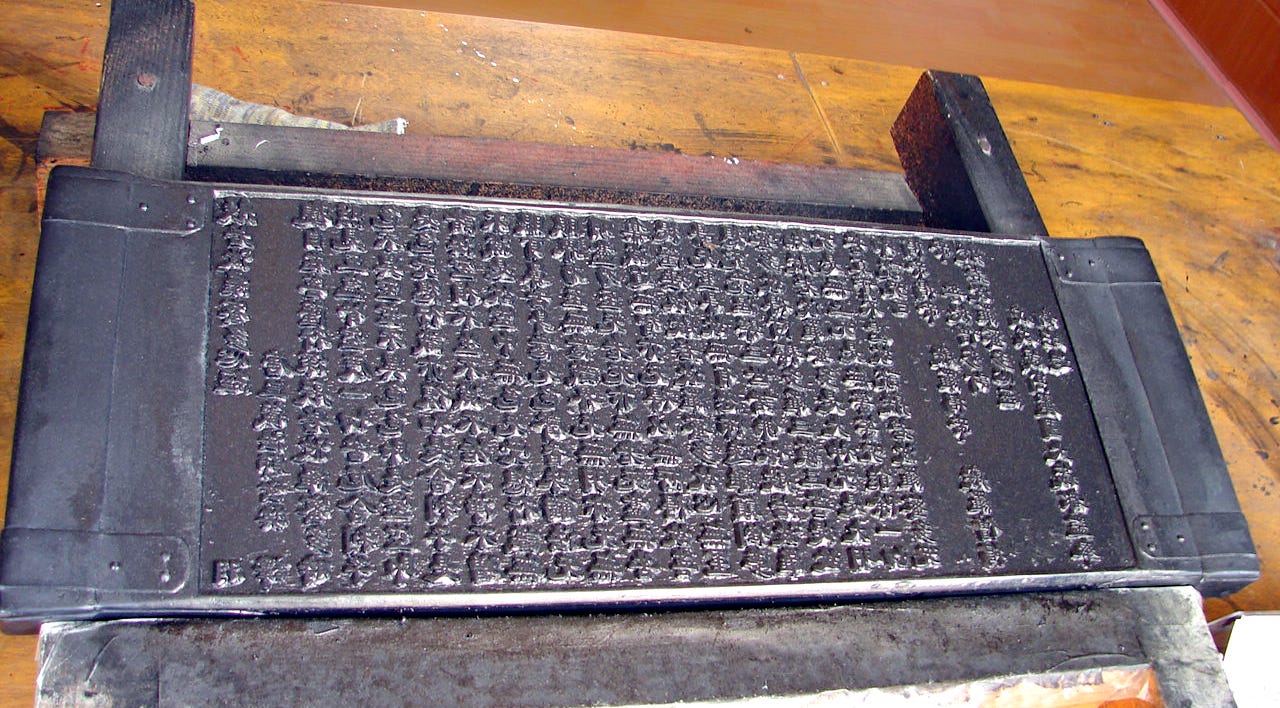

A rather brilliant story of one of the earliest known printmakers was a chap called Gong the Sage, who said a supernatural being gave him a magical jade block, where he needn’t require a brush but to simply blow on the paper and characters would appear, as if by some kind of sorcery. This Gong chap would use this magic to create a shroud of inky mystery around his name, bewildering on-lookers. The air of spiritual happenings within printmaking didn’t end there. But the influence of Buddhism in this period greatly pushed the art form, being produced in temples. Buddhist texts were said to have Talismanic properties of sacred power to ward off evil spirits. Initially due to the sacred nature of these texts, they weren’t meant for widespread public consumption but were scrolls placed in consecrated ground which had Buddhist Spells written on them. It is interesting to see, that as always, something of a spiritual and religious nature is the reason for the spread of information and advancement of technologies. The woodblock technique spread and was utilised for other purposes. Blocks were carved for encyclopaedias, poetry, history, philosophy, medicine etc… For scope of the production time, it took 10 years to carve 130,000 blocks of text for the Tripitaka Buddhist script in 971AD. As a comparison, for the Christian scribe, it would take between two to three years to write the text of the Bible single-handedly. The old way of making books was a very patient game!

With the growth of the production, publishing houses were established and oh boy were they produced. Today we complain about the impact of social media and tiktok on our youth, yet back in the year 1076 one 39 year old Su Shi remarked upon the unforeseen effects of books:

“In recent years merchants engrave and print all manner of books belonging to the hundred schools, and produce ten thousand pages a day. With books so readily available, you would think that students' writing and scholarship would be many times better than what they were in earlier generations. Yet, to the contrary, young men and examination candidates leave their books tied shut and never look at them, preferring to amuse themselves with baseless chatter. Why is this?”

I think the case for literacy and books can be made another time, but for now we stick to printmaking! The techniques of the woodblock spread, reaching Central Asia first, then the Middle East and much later Europe. Perhaps the most well known, and greatly mastered of the woodblock are the Japanese. The art of Japan developed out of Chinese art, in regards to printing, much like the Chinese it was used for the production of Buddhist texts first, and then gradually filtered through to effectively a mass media by the 17th century. This later period is known as Ukiyo-e, which translates to ‘pictures of the floating world’. Now it sounds rather poetic and lyrical, but the floating world referred to the licensed brothels and theatre districts of Japan’s major cities during the Edo period. Geishas, courtesans and actors took to the stage. When we put people on a stage, they become icons. Actors and courtesans became the fashionistas of the day and their trends spread through woodblock prints. The 17th Century Instagram influencers, via the woodblock. This allowed mass-produced images, (beautifully made at least!) to be affordable to the hoi polloi. Printing houses and publishing companies were booming, when it came to production you would have the artist creating composition, the carver preparing the plates, and the printer to finish the job. With paintings being out of grasp for many, the single print allowed a piece of art for many, and not only art but many forms of printed ephemera.

Moving on to Europe, paper came to the West in the 11th century via the Middle East into Spain. It was until the 14th century when the paper mills really started their run. As this craft was nurtured and mastered so was the woodcut print. It is hard to trace the history of the woodblock, as they mostly have no date or location of printing on them. But it was in this epoch that mass communication started to truly fly. The method of printmaking fits perfectly for this. This was known as the Popular Print. The term Popular Print was coined in the late 18th Century by scholars, Romantic writes such as Goethe, the Brothers Grimm and Walter Scott saw the dangers of industrialisation and the disappearing of native cultures, seeing the spirit of the Nations of Europe embodied in the lives of peasants and craftsman, the populace. Something which is being eradicated at an alarmingly fast rate today in place of a homogenised global mess. Studying popular or mass culture became an important task, and here we still are doing just so. The term popular print doesn't refer so much to the availability of the prints but really about what everyone would of been talking about in the towns.

The first woodblock prints were used for Religious purposes first and foremost, as these art forms usually start, and also the playing card for a bit of sporting. Woodcuts of both high and low quality appeared in Germany and France soon after 1400. These were very direct, bold and rather beautiful even though they are seen as a bit crude. Due to the reproducibility they spread like wild fire. Prints of Saints, Christ and the Virgin Mary were sold in huge numbers. The prints were used for veneration and devotionals at home, sold to pilgrims, some were pasted onto travelling chests and frequently sewn into clothing to protect you from the conniving demons tapping on your shoulder.

Part II Coming soon….

Fascinating stuff. And there was the change in reading in the West just before printing. There is a mini thesis by Ivan Illich about early 12thC Hugh of St Victor; 'In the Vineyard of the Text' available online. 'We' did not know 'silent reading'; it had to be re-invented. Illich wonders if we are reaching the end of the 'bookish era' that followed. I am impressed by the survival of icons (I guess we use the term a bit loosely these days). I worked in what is now N Macedonia at the end of the 90s and was impressed by the continuing role of icons, whose design and painting had come very late because of the isolation and peaked at the end of 18th and beginning of 19thC. Wood block you show to be well suited for this representation and to my mind has a durable future!